|

1. Introduction

In the following we assume that the reader is acquainted with the previous article [1] which has introduced the concept of a Generalized Heronian mean Her(k,a) of rank k of an n-tuple a = {a1,a2,...,an} of non-negative real numbers.

It has been conjectured that Her(k,a) satisfy the inequalities

(1) A(a) ≥ Her(k,a) ≥ Her(k+1,a) ≥ Her(a) ≥ G(a),

where A(a) and G(a) are the arithmetic and geometric means of a, respectively, and Her(a) = limk→∞Her(k,a) is the Hermean of a.

This article does not provide a general proof of these conjectures but analyzes their validity for a few special cases.

It also derives an explicit expression for the Hermean in the case n = 2.

2. Special case: any n and k = 1, 2

Since Her(1,a) = A(a) is a trivial case [ref.1, Section 2], we will concentrate on Her(2,a) and show that, for any a,

(2) A(a) = Her(1,a) ≥ Her(2,a) ≥ H(0.5,a) ≥ G(a),

with the equal sign valid if and only if all the ai values are identical.

Here H(0.5,a) denotes the Hölder mean H(p,a) with p = 0.5 (reference [2, Eq.4]) and, since H(p,a) ≥ H(0,a) = G(a) for any positive p, only the first two inequalities in (2) need to be proved.

Proof:

First, let {x1,x2,...,xn} be any set of real numbers.

Consider the trivial inequality

(3) Σi,j (xi - xj)2 ≥ 0

which is sharp unless all xi are equal. Expanding the square, one easily obtains the elementary (but important) inequality

(4) n Σi xi2 ≥ Σi,j xixj

which will become our common starting point for proving the first two inequalities of (2).

First inequality of (2)

Add Σi xi2 to both sides of inequality (4) and rewrite the RHS as follows:

(5) (n+1) Σi xi2 ≥ Σi xi2 + Σi,j xixj = 2 Σi≤j xixj.

Finally, divide both sides by n(n+1) and replace, with no loss of generality, each xi by √ai. The result is

(6) ( Σi ai ) / n ≥ ( Σi≤j √ai√aj ) / (n(n+1)/2)

which, according to the respective definitions, amounts to A(a) ≥ Her(2,a), QED.

Second inequality of (2)

Add n Σi,j xixj to both sides of inequality (4),

(7) n ( Σi xi2 + Σi,j xixj ) ≥ (n+1) Σi,j xixj,

and rewrite each side as follows:

(8) 2n Σi≤j xixj ≥ (n+1) ( Σi xi )2.

Now divide both sides by n2(n+1) and, again, replace each xi by √ai. The result is

(9) ( Σi≤j √ai√aj ) / (n(n+1)/2) ≥ [ ( Σi √ai ) / n ]2,

which, according to definitions, amounts to Her(2,a) ≥ H(0.5,a), QED.

3. Special case: any k and n = 2

We will first assume that at least one of the two elements of a = {a1,a2} is non-zero; with no loss of generality, this condition will be applied to a2. By definition [1], the Heronian mean Her(k,a) evaluates in this case to

(10) Her(k,a) = ( Σi=0:k a1i/k a2(k-i)/k ) / (k+1) = a2 ( Σi=0:k wi/k ) / (k+1), where w = a1 /a2.

When a1 and w are positive, the function f(x) = a2 wx is convex. Considering the x-values interval X = [0,1], we recognize that the theorem of reference [3] is directly applicable and gives Her(k+1,a) ≤ Her(k,a), thus proving that the sequence Her(k,a) is non-increasing. Equality applies only when a1 = a2 = c have the same value, since then Her(k,a) = c does not depend upon k (this covers also the case when a1 and a2 are both zero). Finally, when a1 = 0, we have H(k,a) = a2 /(k+1) which is again a decreasing sequence.

This, for n = 2, completes the proof of the first two of the three inequalities in (1).

The third inequality can be proved as follows, starting from the second expression in (10):

(11)

Here, the expression for Her(k,a)/a2 is first interpreted as the k-th root of the Hölder mean H(1/k,w) of the set of non-negative real numbers w = {w0,w1,w2,...,wk}, then we exploit the notorious fact that H(p,w) ≥ G(w) for any p > 0 and, finally, G(w) is evaluated explicitely, obtaining the desired result.

This completes the proof of the inequalities (1) for n = 2 and any k.

For the special case we are considering, the inequality Her(k,a) ≥ Her(k+1,a) can be proved in yet another way which is actually quite interesting.

For the sake of completeness, let us see how it works out:

An alternative proof that Her(k+1,a) ≤ Her(k,a)

Considering the first equation in (11), to prove the inequality it is sufficient to show that

(12)

Setting w = xk(k+1), this reduces to showing that the k(k+1)-degree polynomial

(13)

is non-negative for any non-negative x.

First, it is easy to see that P(0) = 1, P(1) = 0, and also P'(1) = 0. Consequently, x = 1 is a double root of P(x) and

(14) P(x) = (x-1)2 Q(x).

It would be sufficient to show that Q(x) > 0 for any x > 0 or, since Q(0) = 1, that Q(x) has no positive real roots. Unfortunately, neither Sturm's nor Descartes' rules seem to be applicable, but we will show that Q(x) has only positive coefficients, which is an even stronger affirmation.

If we write the polynomials P(x) and Q(x) in a general way as

(15)

then equation (14) imposes the following relationship between the coefficients:

(16) pi = qi-2 - 2qi-1 + qi

from which one obtains a recurrence defining qi's when the pi's are known:

(17) qi = pi + 2qi-1 - qi-2.

The recurrence (17) can be started assuming q-2 = q-1 = 0 which gives, correctly, q0 = p0 = 1.

As an example, consider the case k = 3 which leads to a 12-th degree polynomial P(x). From (13) and (17) one obtains

p = {1,0,0,-4,5,0,-4,0,5,-4,0,0,1} and q = {1,2,3,0,2,4,2,0,3,2,1,0,0}.

We see that, indeed, all coefficients of Q(x) are non-negative and, as a test, that the highest two are zero.

This has been tested numerically up to k = 10000, finding no exception.

The recurrence (17) can be used to derive a non-iterative solution for the qi:

(18)

In the present case, substituting the coefficients pi according to equation (13), this gives

(19)

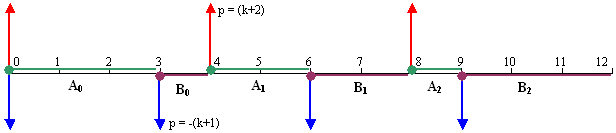

Depending upon the value of i, qi may fall into one of the two types of intervals, denoted as Ar and Br, r = 0, 1, ..., (k-1), and arranged as shown in Fig.1. Explicitly, Ar = [r(k+1),rk+k) and Br = [rk+k,(r+1)(k+1))

Figure 1. Example of the A-intervals (green) and B-intervals (brown) for k = 3

The vertical arrows denote schematically the positive (red) and the negative (blue) coefficients pj.

For index i=0 the two coefficients overlap and the resulting value is p0 = 1 (there are no other overlaps). The coefficient pi at the highest index i = k(k+1) is irrelevant since we know a-priori that the qk(k+1) is zero (and so is qk(k+1)-1).

When the index i lies in Ar, it is preceded (r+1) times by one for which the p-coefficient is (k+2) and (r+1) times by one for which the p-coefficient is -(k+1). We can write it as i = r(k+1)+d, where d = 0,...,(k-1-r) is the intra-interval offset. Using these facts, equation (19) gives - after a somewhat cumbersome evaluation - the following simple result:

(20)

which is clearly positive.

Vice versa, when the index i lies in Br, it is preceded (r+1) times by one for which the p-coefficient is (k+2) and (r+2) times by one for which the p-coefficient is -(k+1). We can write it in this case as i = rk+k+d, where d = 0,...,r is again the intra-interval offset. Substituting these data into equation (19), its explicit evaluation gives

(21)

which is non-negative.

We have therefore proved that all the coefficients of Q(x) are non-negative and Q(x) is positive. According to equation (14) this means that P(x) is always positive except when x = 1 in which case it is zero. Due to the argumentation preceding equation (13), this implies Her(k+1,a) ≤ Her(k,a), with the equality holding only when a1 = a2 (equivalent to w = 1 and x = 1). QED.

4. Summary and final remarks

The first special case shows that, for any finite set a of non-negative real numbers, Her(2,a) is, as conjectured in [1], smaller than Her(1,a), while remaining greater than the geometric mean G(a). Incidentally, for the latter part of this statement, we have proved a much stronger inequality, namely Her(2,a) ≥ H(0.5,a), where the RHS denotes the Hölder mean H(p,a) with p = 0.5.

Combined, these results amount to:

(22)

valid for any set of non-negative real numbers {a1,a2,...,an}. The equality signs apply if and only if all the ai have the same value.

The second special case proves the conjectures of reference [1] for sets a of two elements.

Explicitely, the present results can be written as

(23)

valid for any non-negative real numbers a,b and any integers k,K such that K > k ≥ 1. The equality signs apply if and only if a = b.

By showing that the sequence Her(k,{a,b}) is monotonously non-increasing and has the geometric mean G(a) as a lower bound, it also proves that it has a limit and the Hermean Her({a,b}) = limk→∞ Her(k,{a,b}) exists and is not smaller than the geometric mean of {a,b} (its actual value will be discussed in the next article of this series).

5. Addendum

This is an a-posteriori addition (of Oct.14) motivated by the fact that I have recognized that the inequality Her(k,{a,b}) ≥ G({a,b}) can be proved in a more elementary way than the one indicated by equations (11). I append it here as a kind of post-scriptum.

Start with the elementary inequality

(A1)

valid for any positive x and sharp unless x = 1.

From (A1) it follows that, for any integer k >0 and any positive z,

(A2)

(to see this, simply pair the terms for i and k-i and apply (A1), distinguishing between odd and even k's).

The latter inequality sets a well known lower bound on the value of any finite geometric series:

(A3)  . .

This, however, is not what interests us here.

Since (A2) holds for any positive z, it holds also for z = x/y, where x and y are any positive real numbers. Hence

(A4)

Now multiply both sides by (xy)k/2/(k+1), obtaining

(A5)  . .

The first few special cases of these inequalities are

(A6)

but this, again, is not what concerns us here.

Since the k in (A5) is a constant and x, y are positive but otherwise arbitrary, we can set x = a1/k and y = b1/k,

where a are b are arbitrary positive numbers. This gives

(A7)

which is the result we wanted to prove.

|